On Afro-Indigenous Solidarity

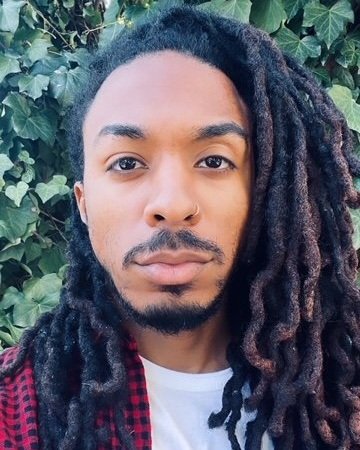

By Jared Davis

This blog post contains the personal opinions and reflections of the author and is not representative of the voice of the organization.

By Jared Davis, Administrative Associate at Black Farmer Fund

This Indigenous People’s Day, I want to reflect on the complex relationship between Black folks, land, and the First Nations of our country. Within the scope of racial capitalism, (Black) Africans and the Indigenous peoples of the world have inarguably lost to the system of exploitation under which we collectively exist today, despite having contributed lives and labor to benefit those in power. I believe that deeming who suffers the “most” under systems of exploitation is a useless endeavor: indeed, we all lose when injustice is perpetuated. In carving out spaces for ourselves in a world in which we were never meant to thrive, harm has been perpetuated between Black Africans and the Indigenous of the Americas, as has so much care. How can we reflect on this troubled history and imagine constructive ways towards a new chapter in our shared history – one of resistance to the oppressive mechanisms of white supremacy and racial capitalism? We do not need to exist in conflict with one another. Indeed, a roadmap for Afro-Indigenous solidarity has long existed, and we only need to listen to the wisdom of our forebears to continue along that path.

“We cannot change the past, but what we can do is actively work toward a future that works to not only undo historic harm but celebrate the long history of solidarity between Africans and First Nations in the Americas.”

It’s useful for me to acknowledge that the very intentional work of racial capitalism is to create groups across which those in power force the marginalized to hoard resources, and lines of distinction must be drawn. I touched on this in my earlier blog post and want to return to this notion here: If I am Black, I must therefore look out for “Blacks”...If I am Indigenous, I must therefore look out for my tribe, band, nation, etc.

However, as much as this may be the reality with which we’ve been saddled, life is much messier than this. In buying into hard and fast rules concerning identity, we erase those who exist at intersections. When I speak about Afro-Indigenous solidarity, I do so through the prism of our shared historical realities and not simply through the lens of monolithic identities. Suppose we reject the historiography offered to us by the Eurocentric academy. In that case, we realize that Afro-Indigenous relations have existed long before the transatlantic slave trade and that those relationships continue to exist despite, and not because of, the ongoing reality of that history in the Americas today. Nonetheless, we must acknowledge the fractures.

Both Africans and the Indigenous of the Americas are marred by a shared history of dehumanization, albeit to different extents and ends. Africans (as expressed so eloquently by Cedric Robinson in Black Marxism) were disfigured through the process of racialized enslavement. This process situated our ancestors as a source of free labor toward constructing the so-called “New World.” Our ethnic or tribal identities were stripped of us, resulting in our transformation into “Blacks” and, ultimately, the commodification of our bodies to be regarded as chattel or movable goods. Conversely, the dehumanization of First Nation peoples facilitated and justified the expropriation of once indigenous communal lands and the transformation of the Americas into colonial settler societies (of which “Blacks” were to build from the ground up).

Consequently, both identity groups, to survive, have had to cope with a status quo in which they were never meant to take part. Indigenous peoples’ participation in the enslavement of Black Africans and the perpetuation of anti-black racism bred as a result of that experience. And Africans, through continued settling, purchase, and normalization of existence on stolen land. Neither group asked to be involved in this cycle of violence, but we would be very remiss not to acknowledge these facts. And yet, it has not been all doom and gloom.

Through intermarriage, armed resistance, the formation of communities that offered an alternative to colonial settler society, and the maintenance of Indigenous and African practices in the face of sustained erasure, Black Africans and the First Nations have been at the forefront of preserving traditional forms of communalism, nature and our ecosystem (long before the advent of the Climate Crisis and the attendant need for “sustainable solutions”).

At Black Farmer Fund, many businesses we have supported with our Pilot Fund operate in the service of these traditions. They use models such as co-operatives, collectives, community-supported agriculture (CSAs), bartering, and other alternatives to the market, prioritizing the needs of the community and the earth first. By shifting decision-making power into the hands of community members, who rarely, if ever, get a say on how resources are distributed, we aim to disrupt the tendencies to compete for resources, offer each other support, and reach common ground, as is an inherent part of not only Indigenous and African community practices but their North American, Caribbean and Latine descendants as well.

Alongside our ecosystem partner, Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust (NEFOC), we aim to repair the harm perpetuated against our communities, not replicate it. We are working alongside Indigenous communities to listen, learn, and be in community with those who carry the original relationships and responsibilities to the land that we now call home. Our shared desire is to connect Black and Indigenous farmers to land to grow healthy foods and medicines for our communities. We plan to accomplish this by acquiring and returning land to Indigenous nations while respectfully connecting Black, Asian, Latinx, and other POC farmers and land stewards to the land while centering and respecting the sovereignty of the original Indigenous stewards of this land. We cannot change the past, but what we can do is actively work toward a future that works to not only undo historic harm but celebrate the long history of solidarity between Africans and First Nations in the Americas.

Happy Indigenous People’s Day!